Delivering Bad News

David Ray Velez, MD

The Operative Review of Surgery. 2023; 1:150-154.

Table of Contents

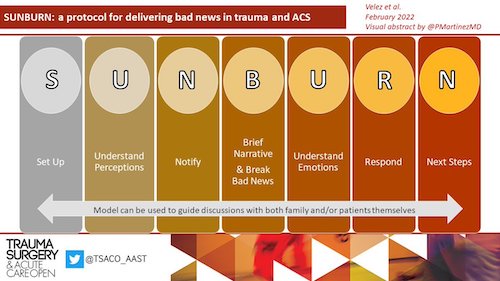

SUNBURN Protocol

Definition

- Framework for Delivering Bad News in Trauma and Acute Care Surgery

- Used to Guide Discussion with the Patient and/or Family Depending on the Circumstances

Steps 1

- S: Set Up – Review the Clinical History and Prepare for the Conversation

- U: Understand Perceptions – Appreciate What information is Already Known and Correct Any Misconceptions

- N: Notify (“Warning Shot”) – “I’m Afraid I Have Some Bad News”, Followed by a Pause to Sink In

- B: Brief Narrative and Break Bad News – Brief Narrative to Provide Context and then Deliver the News Directly

- U: Understand Emotions – Allow for Silence and Appreciate the Emotional Response

- R: Respond – Respond to Patient/Family Emotions with Empathy and Care

- N: Next Steps – Discuss the Next Steps or Strategy Going Forward

Unique Challenges in Trauma and Acute Care Surgery

- “SPIKES” and Other Protocols Poorly Correlate in Trauma 1

- No Previously Established Rapport

- Injury is Often Sudden Unexpected 2

- Events are Shrouded in Misconception 2

- Patients are Generally Younger 2

- Fewer Resources for Grief Support – Often Present on Nights and Weekends (Not Fully Staffed) 3,4

SUNBURN Visual Abstract 1

SPIKES Protocol

Definition

- Framework for Delivering Bad News

- Originally Designed for the Use in Oncology Patients at MD Anderson Cancer Center 2

- The Most Commonly Described Model in Medicine

Factors 5

- S: Setting – Set Up the Interview

- P: Perception – Assess the Patient/Family Perception

- I: Invitation – See What the Patient Wants to Know

- K: Knowledge – Share Knowledge

- E: Emotions – Respond to Patient/Family Emotions

- S: Strategy/Summary – Recap and Decide the Next Plan

Other Models

ABCDE Protocol 6

- Developed for Use in Primary Care

- Factors:

- A: Advanced Preparation – Review History and Prepare

- B: Build a Therapeutic Environment/Relationship – Ensure Adequate Time and Privacy in an Appropriate Setting

- C: Communicate Well – Avoid Medical Jargon and Allow for Silence

- D: Deal with Patient/Family Reactions – Actively Listen and Explore Empathy

- E: Encourage and Validate Emotions

BREAKS Protocol 7

- Developed for Oncology and Palliative Care in India

- Factors:

- B: Background – Review the Clinical History and Relevant Information Before Hand

- R: Rapport – Build Rapport and Allow Time to Understand Patient/Family Concerns

- E: Explore – Determine Patient/Family Understanding of Illness

- A: Announce – Give a “Warning Shot” and Deliver the News

- K: Kindle – Address Emotions as they Arise

- S: Summarize – Summarize the News and Patient Concerns

General Approach

Preparation

- Take a Moment to Compose Yourself

- Anticipate and Understand the Details Surrounding the Event and Clinical Course

- Mentally Prepare What You Will Say

- Bringing an Experienced Nurse Can Be Helpful

- Remove Any Blood-Stained Clothing

Setting

- Use a Quiet Room

- Have a Safety Strategy to Exit the Physical Space in the Case of a Violent Response

- Multiple Family Members Can Be Supportive but Avoid Excessively Large Groups

- Particularly in Pediatric Traumas – Larger Groups May Detract from the Ability to Provide Support to Parents

Delivery

- Sit Down – Do Not Stand by the Door

- Make Eye Contact and Look at Who You are Addressing

- Understand What Information They Already Know to Correct Any Misconceptions

- Begin with a “Warning Shot”

- “I’m Afraid I Have Some Bad News”

- “I Am So Sorry…”

- Be Honest and Direct, Do Not Beat Around the Bush

- Give a Brief Narrative for Context and Then Deliver the News

- If Patient Has Died, Use the Words “Death” or “Dead” and Avoid Euphemisms (“Passed Away”)

- Avoid Excessively Long Drawn Out Narratives that Delay Delivery – There is No Way to Soften the Impact

- Avoid Excessive Technical Information or Unnecessarily Gruesome Details

- Do Not Rush

After

- Allow Silence for Facts to Sink In

- Allow for the Bereaved to React to the News – Varied Reactions May Be Seen

- Provide Tissues

- Touching/Holding a Hand to Comfort is Generally Appropriate but Should Be Considered in Various Social/Cultural Settings

- Avoid Platitudes or False Sympathy

- “You Have Another Son”

- “I Know What it is Like”

- Do Not Concentrate on Yourself

- “I Have a Child Too”

- “You Know, This Isn’t Easy for Me”

- Provide an Opportunity for Family to See the Patient – Even if Injuries are Mutilating, Although Cover Wounds as Able

Debrief with the Medical Team

- “Second Victims” – Traumatic and Adverse Events Can Cause Significant Psychological Distress to the Physicians and Medical Team Providing Care as Well 8

- Consider a Debrief with the Medical Team to Ensure the Emotional Stability of the Staff

- Discussions Should be Led by the Team Leader/Physician as Close to the End of an Event as Possible 9

- Primary Goals of the Discussion: 9,10

- Review What Happened

- Analyze the Team Functioning and Evaluate for Necessary Changes/Improvements

- Create a Feeling of Professional Capability, Resilience, and Trust

- Enable Expression of Feelings

- Screening of Team Members for Acute Stress Reactions

Most Important Factors in Trauma (From the Perspective of Family) 11

- Most Important:

- Attitude of the News-Giver (72% Consider Important)

- Clarity of the Message (70%)

- Privacy (65%)

- Knowledge/Ability to Answer Questions (57%)

- Intermediate Importance:

- Sympathy

- Time for Questions

- Location of the Conversation

- Least Important:

- Attire of the News-Giver (3%)

References

- Velez D, Geberding A, Ahmeti M. SUNBURN: a protocol for delivering bad news in trauma and acute care surgery. Trauma Surg Acute Care Open. 2022 Feb 9;7(1):e000851. (License: CC BY-NC 4.0)

- McLauchlan CA. ABC of major trauma. handling distressed relatives and breaking bad news. BMJ1990;301:1145–9.

- Kieffer WKM, Michalik DV, Gallagher K, McFadyen I, Bernard J, Rogers BA. Temporal variation in major trauma admissions. Ann R Coll Surg Engl2016;98:128–37.

- Smith SA, Yamamoto JM, Roberts DJ, Tang KL, Ronksley PE, Dixon E, Buie WD, James MT, Care WS. Weekend surgical care and postoperative mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Med Care2018;56:121–9.

- Baile WF, Buckman R, Lenzi R, Glober G, Beale EA, Kudelka AP. SPIKES-A six-step protocol for delivering bad news: application to the patient with cancer. Oncologist2000;5:302–11.

- VandeKieft GK. Breaking bad news. Am Fam Physician2001;64:1975–8.

- Narayanan V, Bista B, Koshy C. ‘BREAKS’ protocol for breaking bad news. Indian J Palliat Care2010;16:61–5.

- Seys D, Wu AW, Van Gerven E, Vleugels A, Euwema M, Panella M, Scott SD, Conway J, Sermeus W, Vanhaecht K. Health care professionals as second victims after adverse events: a systematic review. Eval Health Prof2013;36:135–62.

- Missouridou E. Secondary posttraumatic stress and nurses’ emotional responses to patient’s trauma. J Trauma Nurs2017;24:110–5.

- Knobler HY, Nachshoni T, Jaffe E, Peretz G, Yehuda YB. Psychological guidelines for a medical team Debriefing after a stressful event. Mil Med2007;172:581–5.

- Jurkovich GJ, Pierce B, Pananen L, Rivara FP. Giving bad news: the family perspective. J Trauma2000;48:865–73.