Open Abdomen (OA) and Temporary Abdominal Closure (TAC)

Open Abdomen (OA) and Temporary Abdominal Closure (TAC)

David Ray Velez, MD

Table of Contents

Management of the Open Abdomen (OA)

Indications

- Damage Control in an Unstable/Crashing Patient

- Unable to Close Fascia Due to Excessive Edema or Tension – “The Difficult Abdomen”

- Abdominal Compartment Syndrome

- Abdominal Sepsis

- “Second-Look” to Reevaluate Questioned Bowel Viability or Hemostasis

Most Common Etiologies

- Trauma

- Bowel Perforation

- Visceral Ischemia

- Anastomotic Leak

- Nontraumatic Intraperitoneal Hemorrhage

- Bowel Obstruction

- Pancreatitis

Temporary Abdominal Closure (TAC) Devices are Generally Exchanged Every 24-72 Hours Until Appropriate for Definitive Closure

Abdominal Closure Should Be Pursued as Soon as Possible One Medically Appropriate

Volume Status: Minimize Volume Overload and Visceral Edema as Able to Facilitate Eventual Closure – Must Be Balanced Alongside Necessary Resuscitative Efforts

Nutrition: Open Abdomen (OA) is NOT a Contraindication to Tube Feeds – Although Intestinal Discontinuity is an Absolute Contraindication, Early Enteral Nutrition is Still Preferred for Open Abdomen as Able

Mechanical Ventilation: Although Often Indicated for the Underlying Disease Processes, Intubation and Mechanical Ventilation is NOT Mandatory for Open Abdomen (OA) and Extubation When Otherwise Medically Appropriate is Preferred – Decreased Ventilator Days and Risk of Pneumonia without Increased Incidence of Evisceration

Ambulation/Mobility: Early Mobilization is Possible but Controversial (Although Rarely Feasible Due to the Underlying Disease Processes) – Prolonged Bedrest is Associated with Increased Morbidity While Early Mobilization is Associated with Improved Outcomes but There is No Definitive Evidence to Guide Mobilization with an Open Abdomen

Increased Risk for Hypothermia and Close Attention Should Be Paid to Body Temperature

Temporary Abdominal Closure (TAC) Techniques

Negative Pressure Wound Therapy (NPWT) – Use of a Negative Pressure System to Assist in Closure

- The Most Common Approach for Temporary Abdominal Closure

- Commercial Systems Include AbThera and VAC Therapy

- Suctioned at 100-150 mmHg

- More Expensive but Provides Excellent Fluid Control

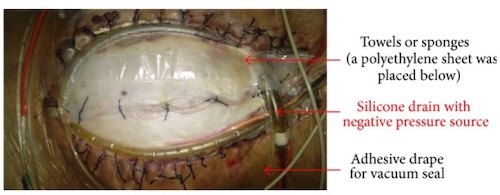

Vacuum-Pack (Barker’s Technique) – The “Home-Made” NPWT System (“Ghetto-VAC”)

- Technique:

- A Nonadherent Sheet is Placed Over the Abdominal Viscera Beneath the Anterior and Lateral Abdominal Walls to Protect the Underlying Bowel

- Add Intermittent Perforations Through the Sheet to Promote Fluid Absorption

- Options: Polyethylene Sheet, “10/10” Steri-Drape, X-Ray Cassette Cover

- A Surgical Dressing (Towel/Sponge) is Placed Over the Sheet

- Two Silicone Suction Drains are Placed Along the Dressing to Allow Negative Pressure

- An Adhesive Sheet (Ioban) is Covered Over the Wound and Skin Edges

- A Nonadherent Sheet is Placed Over the Abdominal Viscera Beneath the Anterior and Lateral Abdominal Walls to Protect the Underlying Bowel

- Suctioned at 100-150 mmHg

- Uses Cheap Material Already Found in the OR if Other NPWT Systems are Unavailable

Direct Peritoneal Resuscitation (DPR) – Instillation of Dialysate into the Peritoneal Cavity to Improve Blood Flow and Decrease Inflammation and Edema

- A Newer Technique that Seems Promising but There is Insufficient Data to Make Any Definitive Recommendations

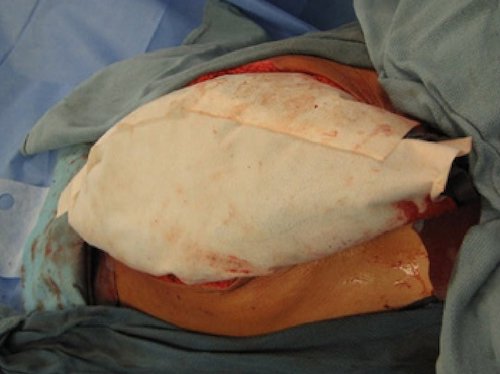

Patch Closure – Use of a Synthetic Mesh Bridge Between the Fascia

- Options Include PTFE Mesh or a Wittmann (Velcro) Patch

- Can Additionally Use a WVAC Over the Patch

Bogota Bag – A Sterile IV Fluid Bag is Sutured to Each Side of the Abdominal Wall

Zipper Closure – A Zipper Device is Sutured to the Wound Edges to Permit Multiple Repeated Examinations

Skin-Only Closure – Uses Staples or Towel Clamps Every 1-2 cm to Close Skin Temporarily and Covered with a Plastic Drape

Fascial Traction Techniques – Systems to Apply Fascial Traction to Decrease Tension When Primary Closure is Not Initially Feasible (“The Difficult Abdomen”)

Abthera WVAC 1

Barker Vacuum-Pack 2

Wittmann Patch Closure 2

Bogota Bag 2

Complications

Generally High Morbidity and Mortality for Patients Requiring Damage Control Laparotomy (DCL) with Open Abdomen (OA)

Enterocutaneous Fistula (ECF) – One of the Most Feared Complications of Open Abdomen (OA)

- Incidence is Up to 20% of Patients Requiring Open Abdomen (OA)

- Patients with New Bowel Anastomosis are at Highest Risk

- Etiology is Often Multifactorial:

- The Primary Pathology Necessitating Open Abdomen (OA)

- Iatrogenic Enterotomy

- Anastomotic Leak

- Visceral Edema and Ischemia

- Dehydration

- Exposure of Bowel to Foreign Material of Temporary Abdominal Closure (TAC) Systems

- Adhesions

- Wound Infections

- *See Enterocutaneous Fistula (ECF)

Loss of Domain/Ventral Hernia – Both Abdominal Pathology and the Resulting Massive Resuscitation Cause Significant Edema of the Bowel, Retroperitoneum, and Abdominal Wall with Lateral Muscle Contraction and Loss of Compliance Causing an Inability to Achieve Primary Myofascial Closure

Fluid Loss – Open Abdomen (OA) Can Result in Significant Insensible Fluid Loss with Hypovolemia – Temporary Abdominal Closure (TAC) Systems Can Often Collect and Quantify the Amount of Fluid Lost

Malnutrition/Protein Loss – Peritoneal Fluid Loss is High in Protein (2 g/L) and May Need to Be Accounted for in Nutritional Planning

Infection/Sepsis – Increased Risk of Infection, Intraabdominal Abscess, and Sepsis

Ileus – Abdominal Pathology, Resuscitation, and Bowel Manipulation Can Cause a Temporary Loss of Bowel Function

References

- Alvarez PS, Betancourt AS, Fernández LG. Negative Pressure Wound Therapy with Instillation in the Septic Open Abdomen Utilizing a Modified Negative Pressure Therapy System. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2018 Oct 10;36:246-251. (License: CC BY-4.0)

- Huang Q, Li J, Lau WY. Techniques for Abdominal Wall Closure after Damage Control Laparotomy: From Temporary Abdominal Closure to Early/Delayed Fascial Closure-A Review. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2016;2016:2073260. (License: CC BY-4.0)